|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

The illusion of “normal.”

The idea of the “return to normal” is an illusion following the devastation caused by Hurricane Melissa. The powerful Category 5 hurricane disrupted the lives of 1.5 million Jamaicans, more than half of the island’s population.

Hurricane Melissa struck Jamaica’s southwestern coast on Oct. 28, 2025, with sustained winds reaching 185 mph and gusts up to 252 mph—the strongest ever measured in a tropical cyclone. The devastation was unprecedented. Forty-five people died and 18 remain missing. Approximately 215,000 buildings suffered major to severe structural damage, while another 156,000 have varying degrees of roof damage. Over 600 schools were severely damaged or destroyed. More than 540,000 customers lost electricity, and the water authority faces losses exceeding CA$86 million.

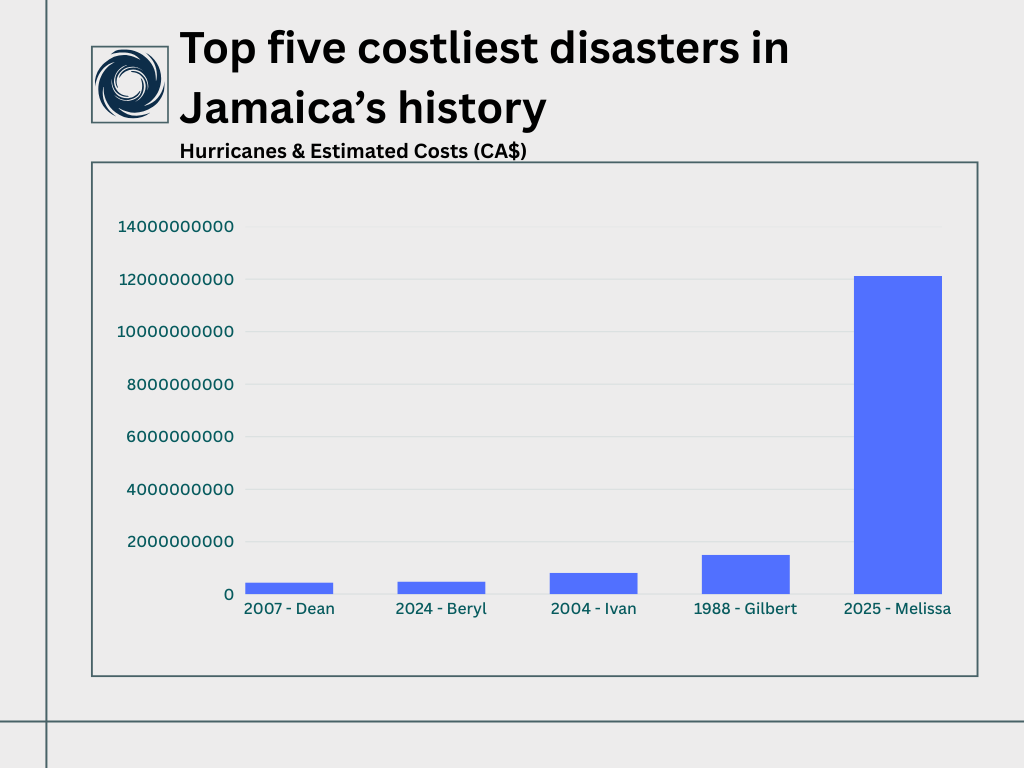

Economic impacts are staggering: agriculture suffered catastrophically, with $259 million in damages, over 40,000 hectares of farmland destroyed, and 1.25 million animals lost. The seven hardest-hit parishes represent three-quarters of Jamaica’s agricultural output and nearly 90 per cent of tourism infrastructure. The World Bank estimates nearly $12 billion CAD in total damage, making Melissa the costliest storm in Jamaica’s history. This figure is equivalent to 41 per cent of Jamaica’s Gross Domestic Product for 2024.

Figure 1.1 Shows the top five costliest disasters in Jamaica’s history. Source: The World Bank GRADE report – November 2025

The crisis exposed critical infrastructure vulnerabilities across Jamaica. The electrical grid, designed to withstand only Category 3 hurricanes, proved inadequate for increasingly intense storms. Building standards were clearly subpar, as extensive damage affected both new and old structures throughout the country. The road network suffered particularly severe impacts, with 396 roads damaged and at least 40 percent of all buildings and roads on the western part of the island, including Montego Bay, sustaining significant damage.

With consideration of the magnitude of the disaster, what is the “return to normal” or “the re-establishment of normalcy” as put forward by prime minister Dr. Andrew Holness? What if the “normal” systems, attitudes and infrastructure that existed before the disaster are precisely what made Jamaica so vulnerable?

Breaking the cycle: why “normal” is not enough

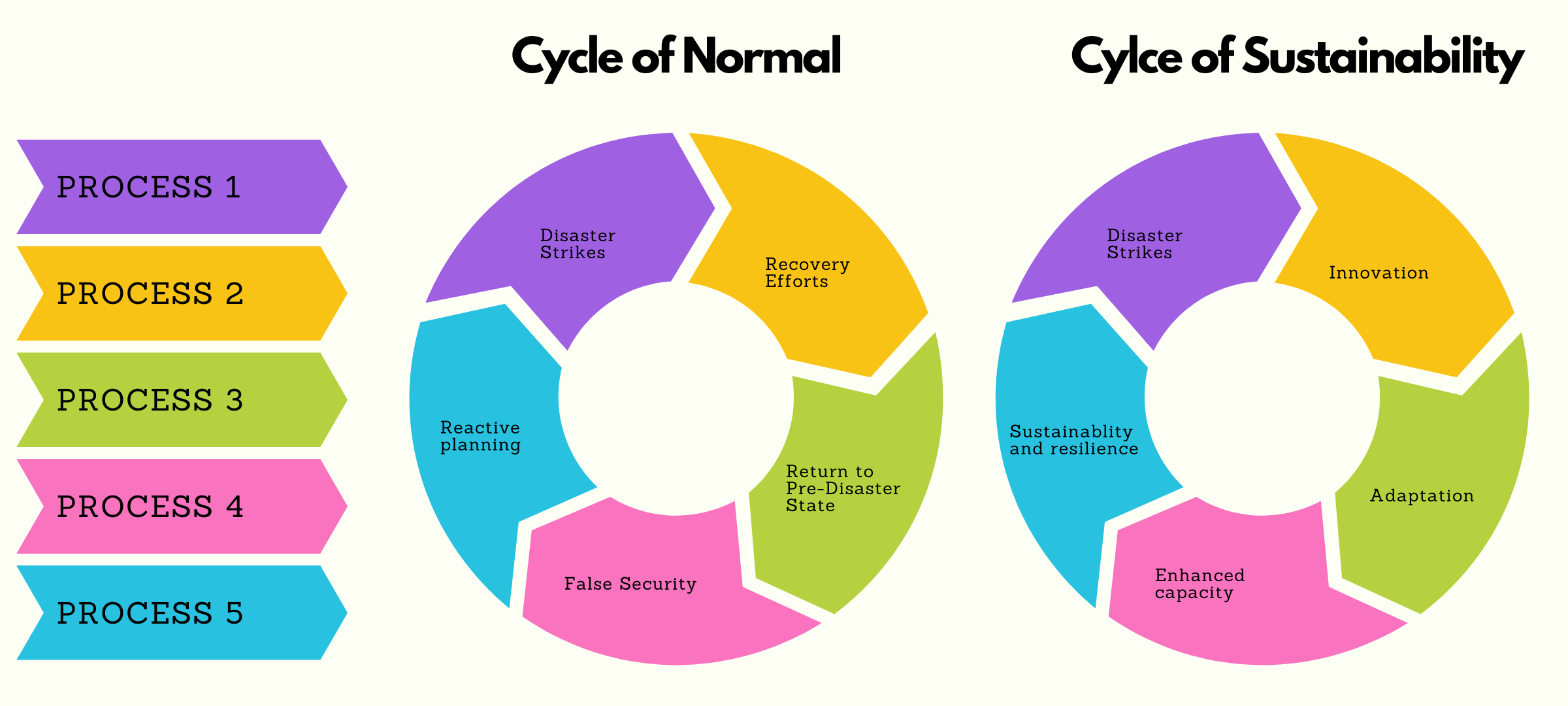

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, normal is defined as “ordinary or usual; the same as would be expected.” Normal creates a cycle which does not lead to innovation. Is this the approach that was been advocated in post-disaster communications?

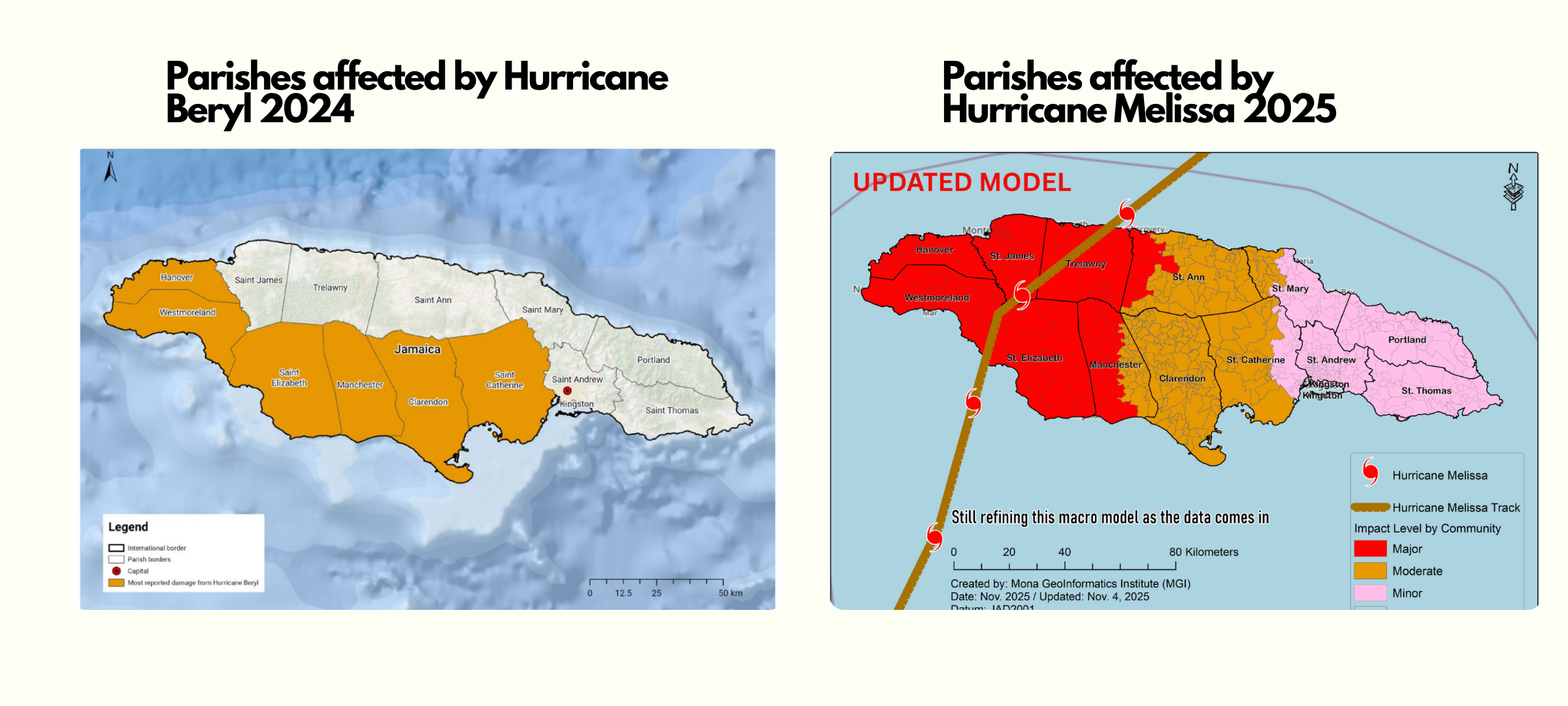

The answer becomes painfully clear when examining Jamaica’s recent history. Prior to Hurricane Melissa, Jamaica had already endured Hurricane Beryl, a Category 4 storm that struck on July 3, 2024, causing an estimated US$345 million in damages. The hardest-hit areas included the southern parishes of Clarendon, Manchester, St. Catherine, and St. Elizabeth, as well as Westmoreland in the west. In the aftermath, businesses and private citizens followed the conventional “return to normal” approach—rebuilding structures to their pre-storm conditions and resuming operations as quickly as possible. However, this reactive strategy proved woefully inadequate when Hurricane Melissa devastated many of these same communities just over a year later. Business owners who had invested their savings and taken on debt to rebuild after Beryl now faced the even more overwhelming task of starting over again, often with depleted resources and diminished resilience. The repeated cycle of destruction exposed a fundamental flaw in Jamaica’s disaster recovery framework: simply restoring what existed before does nothing to prevent the same catastrophic losses when the next major storm inevitably arrives. This pattern of “build, destroy, rebuild” has left affected communities trapped in a cycle of vulnerability, raising urgent questions about the need for more adaptive, forward-looking reconstruction standards that account for the reality of increasingly frequent and intense hurricanes.

Figure 1.2 A side-by-side comparison shows the parishes affected by Hurricane Beryl in 2024 (left) and Hurricane Melissa in 2025 (right). Source: acaps.org and Mona Geoinformatics Institute.

Post-disaster messaging and recovery priorities should advocate and embrace innovation, climate adaptation and building for sustainability and resilience as the “normal.”

Figure 1.3 Infographic contrasting two disaster response models. One the left is the “Cycle of Normal” and the right, “Cycle of Sustainability.”

In a commentary in the Jamaica Gleaner, Rev. Ronald G. Thwaites said that “after Hurricane Melissa catastrophe, this nation cannot be satisfied to just rehabilitate our head-space and physical infrastructure to what they was before October 28. That political economy and social order was unfair to most citizens. Building back stronger does not only mean more concrete and hurricane straps. It is the opportunity, wrought out of adversity, to fashion astonishing turnarounds at every level.” Innovation must drive the thinking framework.

Land tenure and historical inequities

To understand Jamaica’s vulnerability, one must confront an uncomfortable truth: the nation’s disaster susceptibility is deeply rooted in its colonial past. Phyllando Kelly, a Jamaican urban planner and project manager, explains the historical dimension that mainstream disaster discourse often ignores: “Jamaica’s economy and social realities are a product of slavery. It is the history of slavery which determined where newly freed slaves lived, work and socialised.”

This historical legacy manifests in disaster vulnerability. “It is not an accident why there are so many informal communities in Jamaica,” Kelly says. “As former slaves, land ownership was difficult because they couldn’t afford land. Land ownership built generational wealth and so fast forward to today our generation is still struggling to get land tenure. So they end up squatting or live on gully banks and generally unsafe areas.”

The consequences are devastating during disasters. “In natural disasters such as hurricanes, the most destruction occurs where people were living in shacks under the illusion that they were houses,” Kelly says, “and the reason for this is that in most cases they have no land tenure therefore they are unable to build permanent structures.”

Black River, one of the towns hardest hit by Hurricane Melissa with approximately 90 per cent of structures damaged, illustrates both the depth of the problem and the opportunity for transformation. This historically significant town, the first in Jamaica to receive electricity, now faces a blank slate that could either perpetuate old vulnerabilities or pioneer new models of resilience.

Kelly says that reconstruction priorities must address this foundational issue: “In my opinion the reconstruction priority must be land ownership followed by zoning and building standards enforcement. The reconstruction can then take place in a systematic way with funding from government or private organisations.”

Beyond land titling, Kelly identifies another structural barrier: “Jamaica has a fairly large informal economy. There is therefore a need to bring these persons into the formal economy so that in times of disaster these persons can better access government assistance.” He proposes policy incentives including property tax breaks and reduced transfer taxes to encourage formalization, which would simultaneously strengthen disaster preparedness and recovery capacity.

The technology imperative

Andrew Williams, president and founder of Thirsty Tech Inc., approaches the reconstruction challenge from a technology and systems perspective. His assessment is blunt: “There are a lot of technologies, sensors, reporting systems, tools that can predict, but not only that, help to plan for infrastructures that can withstand this. One thing I’ve seen time and time again with each and every hurricane that comes along, it’s wiping out systems that when you take a look at it, it’s just the same old, same old infrastructure that they put in place. You’re not rebuilding it for longevity. You’re not rebuilding it to sustain.”

The repeated failure of Jamaica’s electrical grid exemplifies this problem. Despite assurances before each storm, the network consistently fails, leaving hundreds of thousands without power for extended periods. Williams advocates for fundamental design changes: “If you put a cell tower in place and that cell tower comes down, you’re taking communications out for a specific region or a part of the area. If you run it from a mesh framework where you’re putting antennas within the town on smaller structures that allow it to spread, so if one goes down, the other ones can actually pick up, you need to build that not only into your communication systems, but also into your electrical.”

Recent developments signal some recognition of these needs. Digicel’s partnership with Jamaica North-South Highway Company for an underground duct sharing agreement, represents progress, though Williams emphasizes that underground infrastructure must be part of a comprehensive approach: “Underground cabling seems to be it. Now, with that comes an expense that is perceived to be more expensive than going with your traditional tower. However, when you think about it, if you were to calculate the cost to rebuild Jamaica every time something happens and the cost it would take to continue to rebuild Jamaica if we keep following the same pattern, you are coming closely in line with what the cost would be to do it properly.”

Williams offers a principle that could guide reconstruction decisions: “You build it once, you cry once, but then you live forever. A lot of people want to be able to build it in a substandard way that’s affordable, and then, you know… I’ll just say you build it once and you live in sustainability forever versus building on a budget and having to repair it and fix it—that’s going to far outweigh the costs if you just did it right the first time.”

A Caribbean solution through regional cooperation

Williams proposes an innovative approach to the resource constraints that plague individual Caribbean nations: regional cooperation anchored by less hurricane-vulnerable territories. “I came to some thought because I was thinking, if you take a look at Trinidad, the Bahamas, areas across that coast that are always impacted, and then you take a look at some of the areas that are less impacted—Bermuda, Curaçao—these places, and actually Curaçao is developing itself in terms of IT frameworks and infrastructures that are highly advanced.”

His vision involves a triangular agreement: “Form a coalition or a treaty that gathers together all of the weaker, even more impoverished Caribbean countries to build out policies and frameworks that basically leverage places like Curaçao.” The economic logic is compelling: “What Curaçao would love is to be able to pull from the resources from the US. So therefore, what I’m thinking about is kind of a triangle agreement where we provide our commodities in such a way that it’s more attractive to the US, which would in turn allow us to support Curaçao being our main hub and backbone data centre.”

This model could enable infrastructure investments that individual nations cannot afford alone: “When coming together to build out a framework and leveraging countries like Curaçao and being able to enable a triangle agreement between the US, Curaçao and the rest of the weaker countries, then you’re backing each other up, Caribbean gets what it wants, Curaçao gets what it wants, and in terms of scaling, now you bring it down and it’s easy to budget and easy to plan.”

The concept has resonance for Jamaica, rich in bauxite, rum and agricultural products but cash-poor for infrastructure investment. “If Jamaica doesn’t have money, but they’re high in bauxite, rums, cane sugar—if they work those things out with the US for the US to receive, that allows the US to turn and pour into Curaçao,” Williams explains.

From recovery to transformation

Jamaica faces a choice between perpetuating vulnerability and embracing transformation. Kelly emphasizes enforcement: “Jamaica currently has very good building codes. Enforcement is where we are lacking. Vulnerability is usually a factor of poor economic situation. Therefore, there should be minimum standards that persons should meet in constructing.”

Williams frames it as a mindset shift: “I’m a firm believer that every day presents the opportunity to think differently, to react differently, implement differently.” He warns against the familiar pattern: “I look at this as a chess match with these storms coming on a regular three to five year basis. These recurring storms are always beating us in that game. So how do we structure ourselves to be able to withstand any of the impending storms that come for years to come?”

The path forward requires confronting uncomfortable truths about how historical inequities, inadequate governance, and short-term thinking have compounded natural vulnerability into systemic crisis. It demands investment in underground infrastructure, enforcement of building codes, land tenure reform and regional cooperation, all financed through innovative partnerships and long-term planning rather than crisis-driven repairs.

Black River’s devastation, tragic as it is, offers precisely the opportunity Rev. Thwaites describes: to fashion astonishing turnarounds at every level. The question is whether Jamaica—and the broader Caribbean—will seize this moment to break the cycle of normal and build the resilient, equitable future that has long been deferred.

Post-disaster messaging and recovery priorities must advocate and embrace innovation, climate adaptation and building for sustainability and resilience as the new “normal.” The alternative is to watch the cycle repeat, each iteration leaving communities more vulnerable than the last, until the very idea of recovery becomes not just illusory but impossible.

Leave a Reply